By Eva Kekou, 4Humanities International Correspondent

Eva Kekou: Can you give us some information about your background?

Areti Damala: I started studying Classics, more specifically history, philosophy, Latin and Ancient Greek, before specializing in Material Culture, or more specifically, Archaeology and History of Art of the Mediterranean. I was lucky enough to follow courses both at the University of Ioannina, in Greece, as well as at the Winkelmann Institute of the Humboldt University in Berlin, Germany. As a student and then as a young professional I had the chance to participate in numerous excavations and work as an intern in museums in several European countries.

During the early stages of my career, apart from working as an archaeologist, I also had the chance to work as an Art History instructor and a lead museum educator. This was an important experience since it allowed me to discover the value of using art and culture as a vehicle for bridging cultural differences by using object-oriented learning in order to elucidate questions that will never cease to preoccupy human beings around the globe. Collaborating with children, students and museum visitors of different ages and backgrounds also allowed me to discover early enough that when talking about culture, art and cultural heritage the borders among the instructed and the instructor often get blurred in a very rewarding, revealing and instructive way.

Back at this time, however, I would have had difficultly imagining that some years later I would learn to use digital media as an additional medium for learning and enhancing the aesthetic and cognitive experiences in art and cultural heritage contexts. So in a certain way, I still think of myself as active in the same domain, although now I use alternative, digital media to assist me in carrying out the same mission: contributing so that we all understand, appreciate and get acquainted with different cultural heritage contexts and cultural objects, artifacts and artworks, thus gaining a better comprehension not only of the world surrounding us but also of ourselves.

EK: How would you define transdisciplinarity and what is its importance to art, science, and technology, in your opinion?

AD: Transdisciplinarity is the sine qua non of our information revolution era. Our everyday life practices in terms of information and communication have not ceased to evolve during the last years. Technology is making giant leaps, influencing practically every existing scientific discipline. The same holds true in art and cultural heritage contexts. The research, collaboration, communication and knowledge dissemination practices of archeologists and art historians have largely changed during the last years. I am nevertheless not certain that today every single archeologist, museum professional or history of art instructor is fully aware of the potential of this evolution. My feeling is that within the domain of design, creative arts and industries more and more universities worldwide are aware of these changes and propose studying programs in Digital Art, Interaction Design and Digital Media.

I am afraid though that this is not yet the case when it comes to the History of Art departments. Within the domain of museum and visitor studies we also observe the very same tendency. While museums start to realize and use the potential of digital media to become more effective both as research institutions and at enforcing the bonds with their visitors, in many countries the curriculum offered in museology and museum and visitor studies does not seem to follow this trend. This is truly a pity because exposing young practitioners in the use of digital media as well as “technologists” in Humanities and Social Sciences could be extremely beneficial for both of these worlds.

Art and cultural heritage still have a great deal to teach us regarding how technology can become more human- and user-oriented as well as more socially aware. Initiatives like the one at the Smithsonian Mobile Learning Institute, financed by the Pearson foundation, which aims to explore the potential of mobile, digital technologies for edutainment and learning in cultural heritage contexts, or research centers such as the Getty Research Institute provide an excellent example of the direction we should privilege. Then we also have the vision of artists, particularly those ones that maintain a very intimate relation with technology. What I find most fascinating there is that through their eyes and vision we witness uses of technology we never imagined or thought of. Maurice Benayoun’s emotion forecast, for example, constructs a real-time cartography of worldwide trends experienced in terms of emotions, taking as an input the keywords that appear in Google News. Virtual and augmented reality protests have been organized and endorsed in spaces where a physical protest is not possible or allowed, as was the case with the “AR Occupy Wall Street” initiative. In this way, terms such as AR activism start to get invented and more widely used. The “uninvited” AR exhibition planned by the international artists collective Manifest.AR in the Museum of Modern Art in New York in October 2010 also provides an excellent example of the shift we are just starting to witness.

EK: What sparked your interest in informatics, communication technologies and digital culture, coming from archaeology?

AD: My initiation in the Digital Humanities started in 1999. That was the year in which a brand new interdisciplinary program got inaugurated at the University of Crete, in Greece, through a collaboration of the Computer Science Department and the Department of History of Art and Archaeology. I was part of the first generation of students that followed this curriculum. We were all lucky enough to follow courses and do our practice not only within the Computer Science department and the History of Art and Archeology Department at the University of Crete, but also in world-class affiliated research institutes such as the Cultural Informatics Centre and the Centre of Mediterranean Studies at the Foundation of Research and Technology, Hellas (FORTH). At that time there were only a few places worldwide where one could get in touch with the best of both worlds. What I still missed, though, was a more thorough comprehension of what ICT technologies and digital media can do not only for museum and cultural heritage professionals but also for the public that visits and follows museums, galleries and artists. This was one of the main axes I decided to delve into during my PhD thesis and internship in Orange labs (formerly France Telecom Research and Development), which at that time demonstrated a first-rate interest in exploring how mobile and digital technologies can be used for sightseeing and museum visiting.

EK: Can you describe the work you do at Cedric?

AD:I am working as a Postdoctoral Researcher in the Interactive Media and Mobility group that specializes in digital libraries, mobile computing, 3D and multimodal interaction and video games (including serious games). The lab has the privilege of vicinity with the Musée des arts et métiers, with which we operate under the same institutional framework, the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers. This provides opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration and joint projects among the lab and the museum. My domains of specialization are the design, conception and evaluation of interactive applications for museums and other cultural heritage environments with a particular interest in mobile multimedia applications, Augmented Reality applications, serious games and edutainment, virtual museums and contemporary artistic creation through the use of Digital Media.

Currently, I am leading CEDRIC’s contributions for the European Research ARtSENSE project while I am also assuring the liaison between CEDRIC and the European network of Excellence v-must. In parallel, I am also teaching the course “Digital Resources in History of Art and Archaeology” at the Paris 1, Pantheon-Sorbonne University as a member of the pedagogical team led by Corinne Welger-Barboza, who introduced this course and is the leading figure behind the influential French blog l’Observatoire Critique.

EK: How different/challenging/rewarding is working and researching in Paris compared to the situation in Greece? How do you experience the academic world abroad, and how does it compare to your experience in Greece? In what ways is research facilitated?

AD: Greece possesses great researchers and teachers and world-class research laboratories when it comes to the use of information and communication technologies for museums, galleries and cultural heritage. I have been lucky enough to collaborate with some of them. And though during these last two years, the Greek research and academic community has faced additional challenges because of the crisis in the Euro zone, the Greek research laboratories have not ceased to make substantial contributions in cultural technology and cultural informatics and to be among the pioneers in this domain.

The state budget, however, has suffered severe cuts, often rendering working conditions even more difficult. Severe cuts in the state budget are also experienced in France. However what seems to be much more developed in countries like France or Germany, thus encouraging research and development, are the links and synergies forged among the state, academic laboratories and universities and industries on initiatives and digital products that will eventually find their way both in the market as well as in the everyday lives of millions of people.

EK: Can you please give us more information about ARtSENSE and Manifest.AR?

AD: Manifest.AR is an international artists’ collective that comprises eight core founding and twenty affiliated members, among whom one common practice is the use of Augmented Reality as an expression and presentation medium.

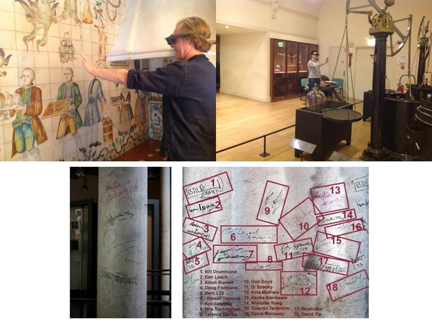

ARtSENSE is a European co-funded research project seeking to explore the potential of Augmented Reality – more specifically Adaptive Augmented Reality – for museum and gallery visiting using a novel optical see-through display that looks pretty much like a pair of glasses. The museum visitor can see the museum objects and artifacts through the glasses, augmented with digital overlays with which s/he can interact with through gesture interaction. ARtSENSE features a transdisciplinary collaboration among academic and industrial research partners and three cultural heritage institutions: the Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas, MNAD (National Museum of Decorative Arts, in Madrid, Spain), the Musée des arts et métiers-MAM (the French National Museum of the History of Science and Technology in Paris, France), and the Foundation for Art and Creative Technology, FACT in Liverpool, UK.

In MNAD the augmented artifact is an 18th century Kitchen from the city of Valencia. The MAM team decided to augment the laboratory and scientific instruments with which Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier used to experiment with the synthesis of water. FACT, in Liverpool, decided to augment the VIP signature pillar, featuring signatures of VIP visitors that have visited or worked with FACT. They also came forward with the idea of exploring the potential of AR not only as a museum interpretation medium but as a medium for proposing visual, Augmented Reality-inspired artworks. For this reason, and under the direction of the FACT project leader Roger McKinley, it was decided to commission one or more artists who would actively participate and collaborate with the ARtSENSE consortium and use several of the technological components developed in ARtSENSE (e.g. user-centred design, acoustics, biosensing, complex event processing, eye-tracking, gesture interaction) to propose a vision of how AR can be used as a brand new creation, expression and presentation medium. After many discussions held within the consortium, Manifest.AR was granted the ARtSENSE commission.

The projects developed by Manifest.AR are presented in the dedicated exhibition “Turning FACT inside out” that was inaugurated in June 2013. The AR interventions of Manifest.AR are not just limited to the gallery building itself but also to the city of Liverpool, thus extending the exhibition beyond the gallery walls and into the city. A more thorough description of how Manifest.AR used and deployed the technologies developed within ARtSENSE is available in a dedicated paper by Roger in the 2013 edition of the Museums and the Web conference. Personally, I consider having the possibility to push our understanding of the potential of AR through the collaboration of software and hardware specialists, psychologists, museum professionals, museum and visitor studies specialists, museum visitors and artists is a real blessing. The active participation of all museum professionals and the unique expressive power of Manifest.AR is really transforming the way we apprehend the potential as well as the current limits of the technologies we are trying to use, thus pushing us to go beyond these limits.

EK: Can you please give us some information about other projects you have worked on regarding museums as interactive educative tools?

AD: The first mobile museum guide project I was involved with was MOBYVISIT. This project explored the continuity of usage when using mobile museum guides in both indoor and outdoor environments. Thus, a mobile multimedia guide was created for the Museum of Fine Arts in Lyon and the city of Lyon itself. More than 500 visitors tested this prototype which, to my knowledge, was the first mobile multimedia guide ever tested in a museum in France.

From 2004 onwards I had the chance to participate in the European funded DANAE research project. The main goal was to explore the potential of dynamic and scalable multimedia content delivered in a variety of different mobile platforms during a museum visit. This prototype was developed in close collaboration with the Museon Museum in The Hague, Netherlands, thanks to the great efforts of the Museon Manager Hub Kockelkorn. Despite the fact that this project was heavily technology-oriented, it was also one of the very first research projects to explore aspects related with the use of mobile media as an interpretational and educational tool in the sensitive museum ecology.

Within the context of my PhD thesis research project I conceived one of the first mobile augmented reality guides for the museum visit for the Museum of Fine Arts in Rennes, France (below).

One of the most important tasks in this study was to monitor and assess the museum visiting experience through direct and indirect observations, interviews, surveys and focus group sessions. Designing and implementing digital, interactive interpretation resources for museums necessitates carefully planned evaluation and assessment sessions in order to figure out the advantages and disadvantages and the overall impact on the museum visiting experience. Museum visitors are not just the end-users of the interactive applications we are trying to develop. They also have their own word to say as to how we can better develop and adapt the technology to their desires and needs.

One of the most rewarding research projects I participated in was the French National PLUG project. PLUG was the first project in France and one of the first on a worldwide scale to examine the potential of mobile edutainment applications and serious games for learning through play in science and technology museums. It featured a multifaceted collaboration among partners coming from museums, industry and academia, both in humanities and sciences, and a very active involvement of the Musée des arts et métiers professionals that played a key-role in the definition of the learning scenarios and the game-design.

Finally, I will always keep an excellent souvenir from CEDRIC’s collaboration with the French painter Olivier Habermann. This was the very first time I had the chance to work closely with an artist. Olivier provided us with the chance of augmenting some of his works with RFID tags. Using mobile phones enabled with RFID readers, the public had the chance to reveal personal comments and annotations about details of the painting, created by Olivier, in the form of text, audio and sounds.

EK: What are your plans for the future?

AD: At a professional level, my wish is to keep active in exploring and better understanding how each museum visit can become an unforgettable experience, with or without the use of interactives. I have to underline however that, to my understanding, the term and notion of the “museum” extends way beyond the museum walls and into the urban and rural environments that surround us.

At a personal level though, and as a European Union citizen who was born and raised in Greece but is living and working in France, I am fully aware of the challenges many colleagues and friends in Greece as well as in Cyprus face on an everyday basis, both personally and professionally. A lesson that many of us have learned is that regardless of any plan we may have for the future, life is often unpredictable. So beyond any plans I might actually envision at the present, my wish and hope for the future is to be finally able to witness a global and universal stability and equality in terms of chances and the possibility to have access to fundamental rights, such as the right to work, gain a decent everyday living, have access to education and medical care in Europe as well as in the rest of the “developed” or developing countries around the globe.