By Eva Kekou, 4Humanities International Correspondent

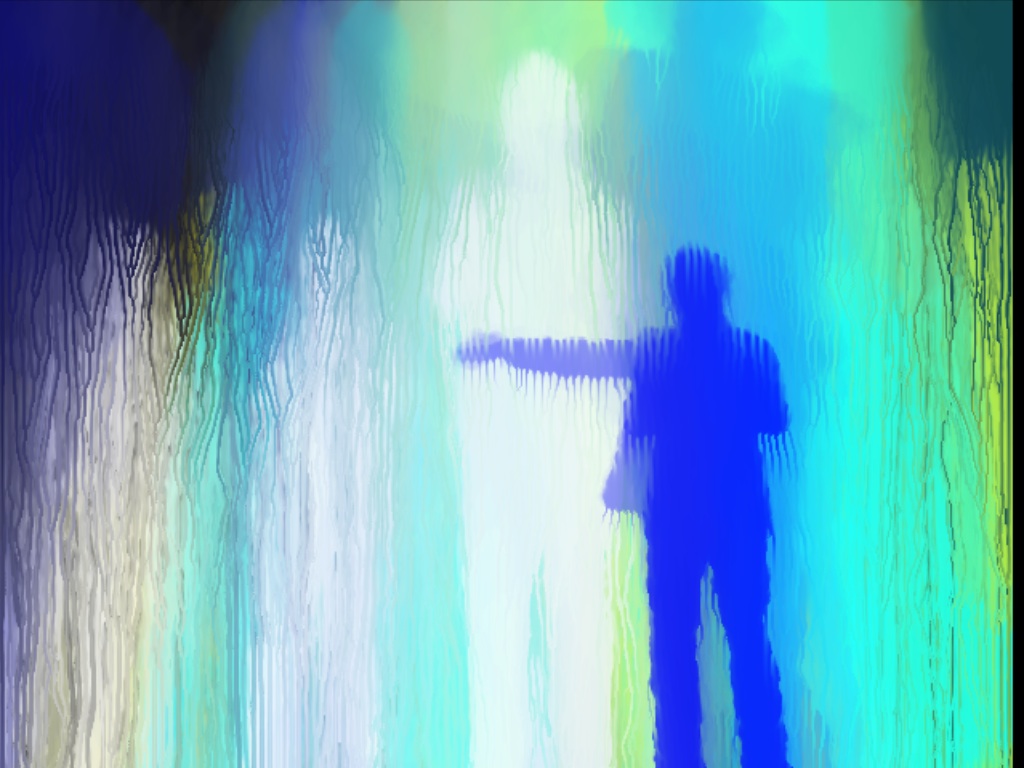

Alex May is a digital artist who utilises his extensive programming knowledge to create his own software for interactive digital artworks and video projection installations that explore our relationship with digital technologies and how human perception of reality can be altered and extended through code and light.

He has performed art at Tate Modern and Watermans, and exhibited internationally including at the V&A, Science Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Caracas, the Science Gallery in Dublin, and the Grande Halle de la Villette in Paris.

Alex is a Visiting Research Fellow: Artist in Residence with the computer science department of University of Hertfordshire and a sessional lecturer at University of Brighton and Ravensbourne.

He is also head of Projective Geometry at The Institute of Unnecessary Research.

Eva Kekou: Can you give us some information about your work and background?

Alex May: I’m a digital artist based in the UK working with light – mainly video projection, programming, and robots. I left education after studying art and computer science at college, as there were no university options available at the time that would have nurtured my interests in combining programming and art. So I got a job developing CD-ROM language teaching courses in the day and spent long nights exploring computer graphics techniques. After about 12 years in the wilderness of business, I discovered VJ’ing – specifically, the ability to react and interpret audio through visuals – and started performing under the moniker of “VJ bigfug” and developing software tools and plugins, something I continue to do today. After a few years, I became increasingly unhappy with clubs as a venue for my visuals and took the step into doing public installations instead, which has developed into my art practise today.

EK: How do you feel about the ways in which video mapping is used and what is different about your software “Painting with Light”?

AM: For me, video mapping is a way of bringing together the physical world and the digital domain. Being able to control light, and therefore visual perception, in real-time and programmatically, allows the artist to take digital data outside of the computer and manifest it in space. Not on a screen or flat wall but contextualised with relevant physical objects so that they become a single symbiotic entity – a digital video sculpture. I think video mapping as a technique has become sadly tarnished by its well-documented use for monumental advertising displays, garishly littered with clichés of crumbling buildings, fields of cubes, and cascading water/fireworks/fish/etc. People talk wearily and dismissively about video mapping because these displays are often all they have seen. So I created “Painting With Light” as a way for artists to get their hands on easy-to-use video mapping software. Traditionally, video mapping requires high levels of technical knowledge and often weeks of preparation. I want to democratise the process, make it much more immediate and dynamic, and put the medium in the hands of artists who want to make art (including myself).

EK: What are your views on digital preservation?

AM: Digital preservation is a fantastically difficult problem that has three parts: 1) preservation of the code/data that comprise the artwork, 2) preservation of the software ecosystem that the artwork runs on, and 3) preservation of the hardware required to run the software and artwork. We have effectively lost so much digital art, as it was never developed and/or stored with longevity in mind. I believe it requires a completely different approach from how programming is commonly taught. When I used to develop code for business use, I would plan for a five-year lifetime, but in an art context, how can we write code that will last 100 years, or 1,000, or more? Emulation of software and hardware is a common and successful solution to entirely software-based artworks, but what of those that require specialist external hardware, such as Kinect sensors or robot motors? I’m developing a software art system at the moment that incorporates most of my digital artworks that keeps them up to date, easily deployable, and abstracts all hardware interfaces. It’s a lot of extra, complicated work, and doesn’t ensure millennium-length preservation, but it’s an avenue worth exploring, and I will be making it available to other artists at some point in the future.

EK: What inspires you?

AM: How technology seems to be diverging from our innate understanding of the physical world is fascinating to me. As someone who understands how computers work, I can see this gap widening, and it’s the bridging of that gap that I want to make art about. I’m not trying to explain how these things work – I don’t back the “everyone should learn to code” campaign – rather, I want to express the fascination I have with the almost invisible mechanisms that are found inside technology. Some of them are at the lowest level of programming, such as memory management, interrupts, and all those good things. I find the Internet inspiring – not the World Wide Web, which is a terribly designed hotchpotch of half thought out ideas with ridiculous competing technical implementations – but the silent TCP/IP protocols, the real Internet, tirelessly delivering data around the world with you barely even knowing it’s there. That feeling that I’m trying to capture is the sound of the phone line when you’re phreaking it – where you’ve fooled the phone system by telling it you’ve hung up the phone, but you haven’t, and you’re left in the void, listening to a machine silence that gives me the same feeling of wonder as looking into the furthest reaches of the night sky.

EK: You started programming at the age of 8 and have done it almost every day since. How has this impacted your art?

AM: I don’t think you have to be a programmer to be a digital artist, which I consider to be creating art with digital mediums, but I think the insights I’ve gained over thirty years of programming experience – everything from assembly language, which is very low-level code, through mid-level languages like C and C++, to high level ones like PHP – allows me to explore the digital as a medium itself. It’s nice to be able to code my art myself, but the process of development also informs the work. I don’t need to have an exact finished work in mind, as I can uncover nuances as I work towards a general direction, sometimes uncovering surprising results, even from terrible bugs in the code that I still manage to create, even though I feel I should know better by now.

EK: Do you see art and code as two separate things? Can code be art?

AM: I’m still struggling with this a little. I was on a panel with several pioneers of digital art (Roman Verostko, Manfred Mohr, Ernest Edmonds, and Frieder Nake) and I started asking questions about where the art resides in the creation of digital art. It is possible, for instance, to write an artwork in a language such as C++ where it first requires processing before it can be run as an application, a process called compiling. Once you have the application, you can effectively throw away the C++ source code and the application will continue to run, so is the artwork in the source code, which has been created by the artist, or the compiled version, which has been created by the computer’s compiler? Also, if you make a copy of that application and put it onto another computer, this is not really a copy, as there is nothing to differentiate it from the original. It is a perfect clone, and independent again from the artist – so where does the art exist then? During the panel, I got increasingly frenetic in my explanation of these questions until I realised that all four artists were just staring at me with a sort of “what is he going on about” look on their faces. I realised at that moment that I’d found an important area for my own artistic research.

It is seemingly rare for code itself to be art but there are examples, such as “Forkbomb Shell” by Jaromil. Additionally, Aram Bartholl produced a “super easy” instructional video about how to turn your code into art, the final reveal being the code he used was a piece of malware employed by the German government to spy on its citizens that had been found and reverse engineered by the Germany’s Computer Chaos Club.

EK: What projects are you are working on at the moment and what are your future plans?

AM: In October, I ran a two-day “Painting With Light” workshop at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Caracas, Venezuela (facilitated by the British Council), where I taught the participants how to use the software. We then created a large scale video-mapped sculpture based on how the participants wanted to represent Caracas. On the evening of the second day this was open to the public as the finale of a month-long series of digital art events.

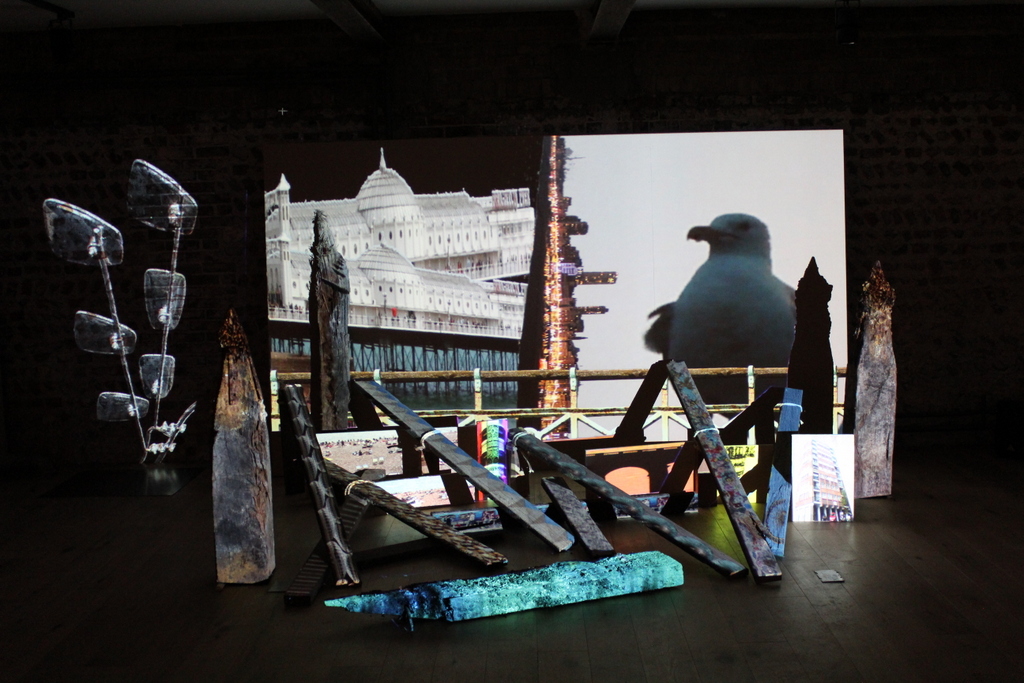

In September, I created another digital video sculpture for the Brighton Digital Festival, which is the city where I live, so it was a very interesting process of revisiting and interpreting a place I’m very familiar with, and quite the antithesis of Caracas, where I had never been before.

I plan to keep developing “Painting With Light”, create more installations with it, and run workshops to show people how to use it. I’m planning a solo exhibition of artworks for next year that explore different aspects of the digital medium, and I’m continuing to develop new software tools for artists.

One thought on “Interview with Alex May”