By Eva Kekou, 4Humanities International Correspondent

Eva Kekou: Hello William! What made you move into the world of computing?

William Latham: It was largely due to having done work in a geometric Russian Constructivist Style, and to producing hand drawn animated films using 3-point perspective when I was 19 – 20 years of age. The sheer labour of producing these films at 25 hand drawn images per sec was a factor in seeking a tool that could help. Initially I did this using Fortran 77 at the Computing Department at Oxford University. One thing that I did learn early on was what a computer can do, and what it cannot. The cannots have changed little since 1982 from my POV.

EK: What was it like being artist in residence at IBM in the 80s?

WL: It was a very exciting period. At that time, machines were slow, you really had to be working in a corporate environment on mainframe computers to be able to do anything interesting. At that time, IBM, which was hugely successful, was backing a lot of innovative research, they were backing Mandelbrot, Alan Norton, Richard Voss, and I felt part of that community. In parallel, Karl Sims was at Thinking Machines and Yoichiro Kawaguchi had commercial backing in Japan, so was an exciting time with artists / science being backed by corporations and that innovation feeding into tech development.

In addition, they were paying me a very good salary to be an artist and sponsoring all my touring exhibitions in the UK, Germany, Japan and Australia, so was an excellent time for me as an artist. On a more minor note, one of the things I really liked in 87 / 88 was that email was quite rare and by being at IBM one had internal email to IBM.

EK: You collaborate with mathematician Stephen Todd – can you describe how that works in practice?

WL: I have collaborated with Stephen for a long time (and now also his son Peter), since 1987, with a gap of around 12 years when I was sucked into the world of developing computer games. The dynamic was first set by Stephen seeing my FormSynth evolutionary drawings, which mapped out an evolutionary system for evolving complex forms. He said, “We should turn this into software.” What emerged was a Mathematician / Artist dynamic, both being very creative, with me as the artist coming up with “big / imaginative vision and having an eye for publicity.”

EK: Can you explain about the algorithms you use in developing your work?

WL: That is quite a big topic! Most of the core algorithms / logic we use today are described in the book Evolutionary Art and Computers that Stephen and I wrote many years ago. There is also a good Evomusart paper we wrote a couple of years ago on the cross-over Bioinformatics work with Imperial College.

EK: You have also been involved in the computer games industry; how did that affect your artwork and vice versa?

WL: I would say the one thing I have learned is organisational skills and how to build software teams to build products and negotiate big contracts. I am now just starting to use these skills again in art and the Phoenix Show backed by The Arts Council England was one my first forays using those skills in art, hopefully be employed many more times.

I think the big thing I learnt from my work in Games, is the difference between Art and Entertainment, is that you cannot do both at the same time. The nice thing about being in the Entertainment industry is that there is a clear measure if something is successful, something sells or it does not, and everything that one does working on a product is to maximise that value. In Art it is more subtle and vague / mysterious and down to critical currents and fashion, which is at times frustrating.

EK: I know you returned to academia after thirteen years. What is the input you can bring in to academia as an artist and from your previous experience?

WL: I would say I have a broad spectrum of experience from hard core commercial through to pure art. I would say I have learned that mixing artists into teams of programmers and mathematicians in a research context produces extremely interesting results and can be a catalyst for real innovation, but then this needs to be rapidly prototyped to be captured.

EK: Give us some information about Phoenix Brighton festival.

What are the aims of the festival?

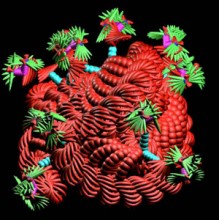

WL: The aims of my show at the Phoenix is to show a full spectrum of work and collaborators: from my early perspective drawings used to make animated films, to my hand-drawn FormSynth drawings done at the RCA, to my IBM work from 87 – 93, then jumping to 2007 when I was at Goldsmiths as a Professor, showing our crossover work with Imperial College in Bioinformatics and other science / art work, to a much more recent large-scale piece, Mutator2 Triptych that fills an entire room, developed over the past year. Overall, I hope to show the history of the work. In addition, I have done a large hand-drawn image directly on the gallery wall, which serves as an entry point to the exhibition. (Great to be drawing again!).

EK: What are your plans after this exhibition?

WL: What has been great about the exhibition is that it has stimulated a reactivation of interest in my Art work. One of my aims is to put on a show of new Retro FormSynth drawings and the show has got me drawing again.

In addition, we will be extending the Mutator2 Triptych to include breed and cross breed functionality for a major group Art show next year.

Post-show, I will be continuing to work on the Crowd Sourced Protein Docking game with Imperial College and Goldsmiths Computing Department and also a new exciting project with the Neuroscience Dep at UCL London.

Overall, I am becoming more and more interested in AI and whether the Artist (or Artist Gardner) could be replaced by a machine as the aesthetic selector, so that the human element is removed. This relates to the work of my close collaborator at Goldsmiths, Professor Frederic Leymarie, since 2007 and his work with Patrick Tresset on Paul, the Drawing Robot. To achieve this, the question is whether a computer could do the Ink Blot test (something to my knowledge which has not been achieved) and recognise the content like a human (e.g., spot the gnomes in the red boots), and then pick and breed forms for itself within Stephen Todd and my Mutator2 System.