By Helen Foley

(reposted from the WhatEvery1Says (WE1S) project site; first published Dec. 1, 2020)

Every time I tell someone I double majored in Economics and English, I receive the same reactions: “Oh wow, what an interesting pairing,” or “Huh. Wow. I wouldn’t have expected those two to go together.” In the simplest terms, the majority of people I engage with have trouble understanding how a “soft” humanities subject like English can connect with a “hard” social sciences subject like Economics due to their preconceived understandings of both fields. In all honesty, when I first came to UC Santa Barbara, I too believed that majoring in the humanities would not be a wise professional investment. I had always loved English, and knew I wanted it to be my primary field of study, but I had been told by my parents, teachers, and counselors that it was unwise to pay for a four year degree and “only major in English.” So, knowing I also found Economics interesting, I decided to pursue both.

However, even after two years of study, I still had trouble understanding how my two majors were connected. In my experience with academia, the contrast between the two was stark. The Economists I met were constantly trying to justify their field as a “hard” science, and took offence when associated with entirely “subjective” “soft” subjects like those of the humanities. In classes I was told that “hard” skills, such as statistical analysis and accounting, were more practical and valuable in the real world. Conversely, I came to believe that the soft skills I was learning in my English classes—critical thinking, effective communication, and empathy—were more valuable in my day-to-day life.

Then I became part of the WE1S team as an undergraduate Research Assistant in the Winter of my senior year, and everything changed. Nowhere have my two disciplines come together more beautifully than in my work in the digital humanities. When I joined the Students and the Humanities Team—working on human subjects research—in January of 2020, I was able to use my experience working in data analytics and statistics to help solve the ongoing problem of tag counting and valuation. During the summer of 2019, WE1S project members had carefully and laboriously hand-tagged hundreds of sources in the WE1S corpus with metadata about their geographical region, media type, and social perspective, but had not yet developed a method by which to use these tags to develop Key Findings. Through teaming up with other experienced researchers in helping to address this difficult problem, I was able to discover how to apply different statistical methods I was familiar with, thanks to my background in Economics, to an evolving research question.

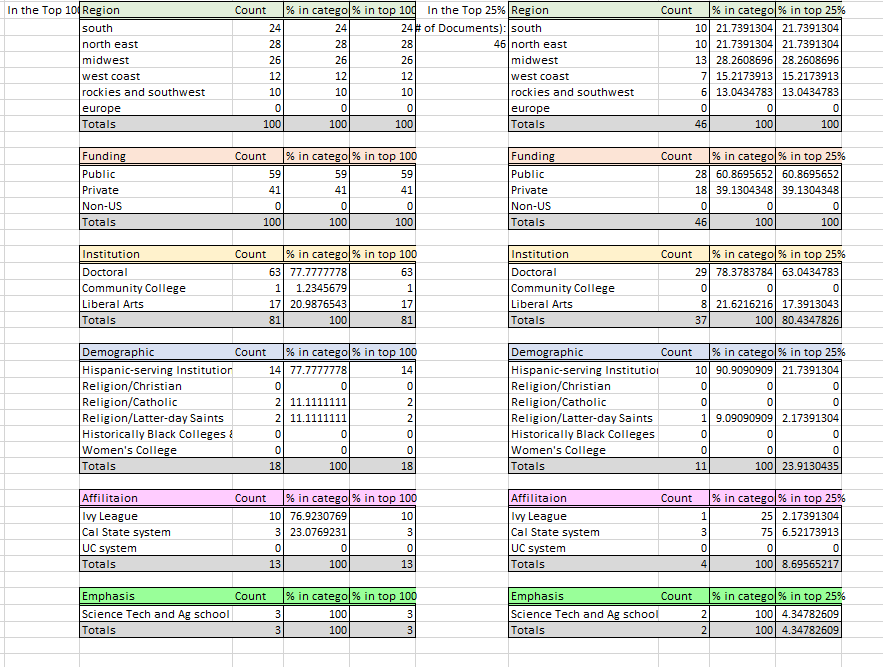

Through trial and error and a laboratory-like environment, I was able to see how the equations from my Economics classes were directly relevant to understanding how language circulates. Working primarily with a topic model of WE1S’s Collection 14 (21,182 articles mentioning “humanities” or “liberal arts” in U.S. campus newspapers), I examined the distribution of tags across topics to understand more fully how topics are related to articles from student newspapers at particular kinds of institutions. Among the top articles1 in each topic, I hand-counted the presence of tags, including “public college,” “private college,” “community college,” “liberal arts college,” “doctoral university,” “Women’s College,” “Historically Black Colleges and Universities,” and “Hispanic-serving Institution,” and calculated their overall frequency.2 With this method, I was then able to use these equations and discoveries to help answer the questions, “How do social issues intersect with student discussion of the humanities?,” and “How do the sciences and the humanities intersect in student journalism?” at different kinds of academic institutions.

The digital humanities—and WE1S—have thus become spaces in which it is no longer “interesting” or “unexpected” that I studied English and Economics, but instead “amazing” and “valuable,” and that has been an incredible gift. Even more exciting, this experience has led to my decision to pursue the digital humanities in graduate school.

I now know that my fields are not only related, but that on a larger scale, Economics and English—and even more broadly, the social sciences and humanities—are inextricably intertwined. This fact is evident not only through my own experience, but also through the Key Findings of this project, such as the fact that the crisis of the humanities has been found to be largely economic, or that the media assesses the value of the humanities economically.

When students are taught that different fields of study are distinctly independent from each other, rather than the countless ways in which they can help inform each other, they are deprived of exciting realms of discovery. WE1S’s goal of initiating opportunities for communication between fields rather than promoting the humanities to the exclusion of other disciplines is only one piece in the larger puzzle of counteracting these destructive narratives. To be part of this movement towards an appreciation for the humanities and the breaking down of stereotypes, the first step is being open to conversation. I have been fortunate enough to have had the opportunity to help facilitate some of these conversations, such as those that occurred as part of the “What’s Your Major: A virtual cross-disciplinary conversation about “major” (mis)conceptions at UCSB” panel in Spring of 2020. Bringing together students from all different areas of study, we were able to facilitate a constructive, candid conversation about the personal experiences of different students in their majors. However, as wonderful as these conversations are in and of themselves, the end goal is larger systemic change. From the restructuring of major systems to allow for greater dialogue and collaboration across fields, to changing the negative narratives surrounding the humanities, there are steps that need to be taken to prevent students with diverse interests—like myself—from missing out on years of exciting learning.

With special thanks to Alan Liu for making my participation in WE1S possible, Rebecca Baker, Ashley Hemm, and Abigail Droge for their kind leadership, Leila Stegemoeller and Jessica Gang for their continuous support, and Scott Kleinman, Lindsay Thomas, Jeremy Douglass, and Francesca Battista for their patience and inclusion throughout my process of discovery.

Notes

- “Top articles” were defined in two different ways. Either they were the 100 articles that contributed the most “tokens” to a topic, or per Francesca Battista’s recommendation, they were all the articles that contributed more than 25% of their tokens/words to the particular topic. See the figure above for an example of analysing a topic using both definitions of “top articles”.

- For related WE1S research, see “Mapping HSIs, HBCUs, Women’s Colleges, and Tribal Colleges” and “Word Embeddings of College and University Mission Statements: Preliminary Findings” by Giorgina Paiella and Su Burtner. Throughout the project, members of Team 3 (Social Groups and the Humanities) have been crucial interlocutors around issues related to metadata tagging.

Joanna (Annie) Swafford ’06, now an assistant professor of interdisciplinary and digital teaching and scholarship at SUNY New Paltz, majored in English and music at Wellesley. “I wouldn’t have my current position if it weren’t for my double major,” she said. “I’m proof that majoring in the humanities can be just as practical as majoring in a STEM field.” A self-professed bookworm who’d played piano and clarinet for years, Swafford’s professional journey began, she said, when she wrote her senior thesis on Ralph Vaughn Williams’ musical setting of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s sonnet cycle, The House of Life. That project brought two of her passions together, but also made her realize that “it was hard for my literary readers to understand my arguments about music, since they didn’t know how to read a musical score,” she said.