By Eva Kekou, 4Humanities International Correspondent

I had the honor of interviewing Scott Kildall and Nathaniel Stern, who both share an immense passion for art and creativity. I am glad we crossed paths some time ago and glad they are my friends now.

Enjoy this interview and Happy New Year!

Eva Kekou: Can you give us some information about your background?

Scott Kildall: I was raised in California as the son of a computer pioneer in the 1970s. My unique childhood included playing text games on servers and my first internet romance at the age of 12 — in 1982!

Fast-forward to my adult years and in my 20s and early 30s, I taught myself to program in C++ and worked in the educational software market for years. I branched into producing social justice documentary videos and ran a metal fabrication studio and then went to art school in 2004, graduating with an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Nathaniel Stern: Following Scott’s lead, I grew up the math geek son of two English teachers, in punk and ska bands from 14 on, singing and playing saxophone. I studied fashion design in college, then went on to do web design and computer art for grad school (at ITP in New York), but quickly got turned on to philosophy and art. That’s where I met Nicole Ridgway – now my wife – and wound up moving to South Africa so we could be together. It was an amazing time, teaching and learning and making work. I haven’t really stopped since, but I’ve gained a lot along the way, especially in how I move with my collaborators. I’ve since written a PhD (soon to be a book!), and now teach at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM).

EK: Was art an outlet for expression? A decision for life?

SK: The funny thing was that when I was in high school and university, the only subject I didn’t care about was art. Until I went to museums as an adult, I had assumed that the subject was about technical proficiency and beauty in the ancient disciplines of painting and sculpture. This held no interest for me.

Once I discovered video art, the conceptual artists of the 1970s, mail art and that the “old” practices of art-marking had conceptual artists working in them, I was hooked. Gradually, I moved away from the structured production environment of documentary video, which felt formulaic, and into art-making involving technology (on some level). Here, I found a challenge, the unstructured dialogue and a warm community of people.

NS: For me, it’s all research. I’ve always been interested in humanity and the humanities, art and the arts, philosophy and the sciences, and how they give us meaning. Whereas the sciences can tell us how to do things, philosophy tells us the stakes, and art gives us an experience of those stakes. I’m invested in all three – but art and experience are most important to me.

EK: How did you two get to know each other?:

SK: We met on the internet! A mutual friend who knew us both and had an interest in networked performance introduced us. Nathaniel was seeking some technical assistance and I ended up helping him out.

This conversation led to him introducing me to his gallery in Ireland, which I later showed with. After months and months of conversation we decided to collaborate on Wikipedia Art.

NS: He is leaving the part out where he got the grant I had originally asked for assistance on, and didn’t get – probably because we decided not to collaborate that time. I did not make that mistake again!

EK: Can you tell us about some of the work you made together and how you both got to these ideas?

SK: We did a couple of small projects together in the online environment of Second Life. We were also both editing Wikipedia articles in 2008. Nathaniel had posted an article on “Scott Kildall” — which had got me started writing articles. I was fascinated with its arcane system. Coming from the point-of-view of a behind-the-curtain programmer and video editor, I understood odd systems well. But Wikipedia was confounding with a thinly-veiled cabal of editors.

NS: Since my first engagements with JL Austen, and later with Performance Studies and then Karen Barad, I’ve been fascinated by performatives in all their forms. The classic definition comes from Austen: words that do things. At a wedding, “I do” makes you a spouse; if I “knight thee,” you are Sir Scott; “declare war” and we are no longer in a state of peace. It felt like anonymous Wikipedia editors wound up having a lot of power – performative power, control of meaning – and we wanted to investigate it artistically. We never knew it would be so big!

EK: I got to know you at Transmediale 2010 in Berlin and was fascinated by your work Wikipedia Art. Can we give some information about it here (concept,work, feedback, how the audience saw this in Berlin and different countries and what they wrote about it, etc.)?

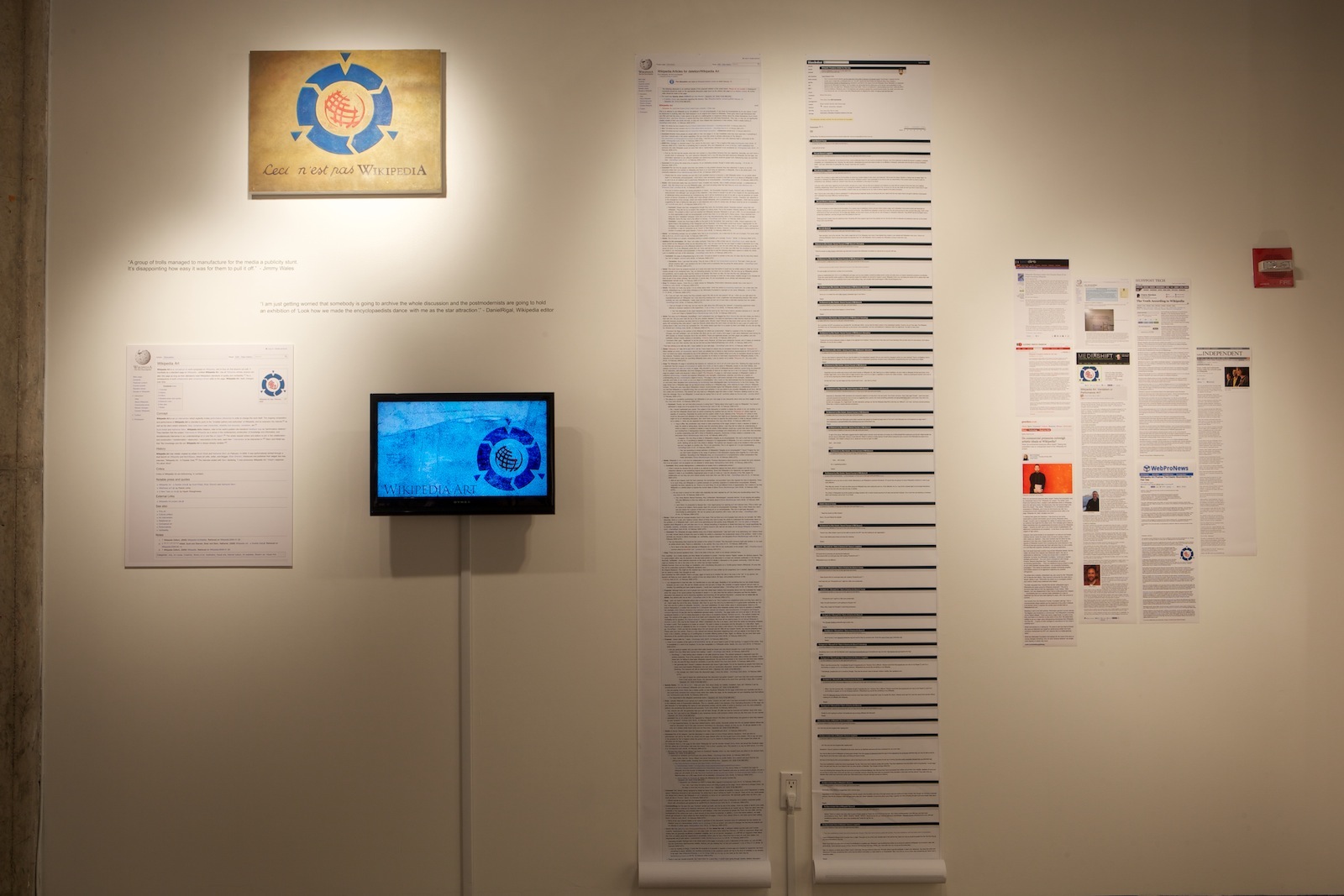

NS: It’s really two works at once. On the one hand, it’s a beautiful art object – an artwork that lives as a WIkipedia page, and is thus “art that anyone can edit”. On the other hand, it intervenes into the hidden power structures of the site.

SK: For an article to be kept on Wikipedia, it has to be verifiable — written about in “legitimate” media sources — but not necessarily true. But since the mainstream media often cites Wikipedia, and Wikipedia must cite the mainstream media, this creates a feedback loop that basically makes us believe the text is true. As alluded to above, we call this “performative citations.”

NS: We targeted Wikipedia’s citation mechanism to reveal the invisible authors and authorities behind Wikipedia. We collaborated with several people to write about the project, post those essays online, cite them on Wikipedia, then post some more, and so – our own feedback loop. It wound up being much more controversial than we expected – 15 hours of intense debate on Wikipedia and about 10 other sites, then hundreds of articles and reposts over the months that followed. We consider all of this a part of the work.

EK: I know Nathaniel has an academic job and Scott is based in California at the center – can you give us some more information about your respective work and some projects you are working on at the moment?

SK: I’ve been working as an independent artist in San Francisco for the last 5 years and also have a job as a new media exhibit developer at The Exploratorium, which is one of the most fascinating science museums around.

The project I am currently working on is called Grantbot, which is a software-trading algorithm with a philanthropic personality that generates arts grants. This is based on the fact that high-frequency trading algorithms make up about 70-80% of all U.S. stock trades. The machines already have a controlling interest in our economy. With the lack of funding in the arts, Grantbot serves as a virtual Robin Hood.

NS: I am an Associate Professor in Peck School of the Arts at UWM, where I teach a range of topics including video art, interactive art, Product Realization (in Engineering), a graduate affect seminar, participatory art, advanced studio courses, and more. My own projects are similarly all over the place – including a lot of collaborating. In the next few months I have a new body of work with Jessica Meuninck-Ganger premiering in Johannesburg and Milwaukee, where we mount translucent prints and drawing to LCD screens, making ‘moving image on paper’; a book on interactive art coming out with Gylphi Limited (London); and I am finishing up a suite of four interactive installations, all made and remade between 2000 and 2013.

EK: I am aware of Scott’s work Playing Duchamp, which is a fascinating piece. Can you give us some information about it?

SK: Marcel Duchamp is an endlessly fascinating personality, who we know as the father of conceptual art. But his lifelong obsession was chess. He achieved the rank of “Master” and even represented the French national team. While he was an amazing player by conventional standards, he was not especially notable by expert players. And thus, showed a sense of vulnerability, choosing to play the game he loved over necessarily making art. There’s still a huge debate about his art vs. chess lifestyle and whether he was playing another game with the art community. As a kid, I was fascinated with chess and even won local tournaments. As an adult, I was lousy at it, but still became fascinated with its notation and understand how Duchamp could have easily fallen for chess.

With Playing Duchamp, I wanted to pay homage to his other life of chess and make a virtual Duchamp chess algorithm which would play chess as if it were Duchamp. Based on his known 72 games of chess, I modified a shareware version of chess code to play in his style. I even consulted with the foremost expert (Jennifer Shahade) on Duchamp’s style of play.

Thus, any artist can “play” Duchamp. I’ve lost every game I’ve played against him. Just like art-making!

EK: What are your future plans?

SK: It’s hard to say for the long-term. In the short term, I am working more and more with algorithms and networked performance. The Tweets in Spaceproject cracked open the possibility of what we can track on the internet in terms of language. I am also exploring some language and image-based work with Augmented Reality based on brainwave sensors in collaboration with John Craig Freeman. I also hope to continue my collaborative work with Victoria Scott, which involves digital fabrication from virtual objects.

NK: I have a few pots brewing. One of my favorites is this ongoing series where I strap a desktop scanner, custom battery pack and laptop to my body and perform images into existence by traversing the landscape. There’s a great image of me going around the Internet, where I’m waist deep, scanning a lily pond! Anyhow, I’m currently working on a marine-rated rig, so I can scan a coral reef. It’ll be some time, but I’ll get there.

Then of course there is our work together! Scott and I do very big projects together, so we have to take our time. Tweets in Space, where we beamed Twitter discussions from participants worldwide towards a habitable exoplanet 22 light years away, took a year and a half of planning, as did Wikipedia Art. We’re still cooling our jets and documenting that one, and I’m sure the next one will flow, bigger and better than the last!